Why Learning Professionals Need to Learn to Speak their Stakeholders’ Language

The language we use is important. There’s no doubt about that. Human cultural development owes a great deal to our ability to communicate complex thoughts and be clearly understood by others so they can take actions.

The language we use is important. There’s no doubt about that. Human cultural development owes a great deal to our ability to communicate complex thoughts and be clearly understood by others so they can take actions.

The problem is, like opinions, there are just so many languages to choose from at any one time. Not just national and cultural languages, but the language of professionals as well.

The independent state of Papua New Guinea, North of Australia, is a good case-in-point. Over 850 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country (12% of the world’s total) among a population of just under 7 million people – an average of around 8,000 speakers per language – with some groups down in the 10s. Imagine trying to work across the country with that challenge and the potential for confusion.

The independent state of Papua New Guinea, North of Australia, is a good case-in-point. Over 850 distinct indigenous languages are spoken in the country (12% of the world’s total) among a population of just under 7 million people – an average of around 8,000 speakers per language – with some groups down in the 10s. Imagine trying to work across the country with that challenge and the potential for confusion.

Professional Languages

But national and ethnic/cultural languages are only the start. If you drop in on a conference or a meeting of virtually any professional group (try pharmaceutical reps, a team of engineers, or a gaggle of Finance people in your own organisation) you’re likely to think that a foreign language is being spoken. That is, unless you’re inculcated into ‘the practices of the profession’ as Bruner calls it. In some ways they are speaking a different language. If we want to understand what they’re talking about we need to spend some time with them and learn it.

Organisational Languages

Exactly the same holds for organisational language. In organisations it sometimes feels as if tens if not hundreds of different languages are being spoken – often for good, practical reasons.

The Finance Department will have its own language, the Sales department will have a different one, and the IT Department often lives out on a limb surrounded by the shield of its own language. Learning and performance professionals will have their own language too – with lots of acronyms, and terms that carry specific meaning – ID, TNA, LMS, HPT and so on, often overlaid with our own organisational acronym set.

This is where lots of problems present themselves for Learning professionals when they attempt to engage with their stakeholders. Many find themselves in situations when the language they are speaking is simply not understood by people in other organisational functions and they, in turn, find difficulty understanding the language of others.

However, if Learning professionals are to work closely with their colleagues and managers in the line of business, whatever that line may be, they need to learn the target language of the stakeholder – and learn it fast.

Some Tactics

I have no particular skills to impart on national and cultural languages. I’m certainly no linguist. So when I find myself in a country where English is not spoken I revert to a couple of basic tactics.

First I look and listen for words that might have some similarity to English. I guess this is a type of pattern-matching approach. I see if there are words that I might understand, check whether the meanings are what I think they may be and store them away for later use.

The second approach involves identifying commonly used words and either asking what they mean or trying to work out their meaning through the context of their use.

Neither of these tactics is as good as learning to speak the language properly but at least I’ve found they help me get by.

An Anecdote

In the early and mid-1980s I spent a number of years working on collaborative ‘eLearning’ projects (although we didn’t know them by that name back then) using computer conferencing technology. I was working with academics, teachers, students and workers in the UK, France and Germany and spent long hours in (physical) meeting rooms where multiple languages were being spoken. In France a lot of the discussion took place in French (naturally). My colleague, a Frenchwoman who had lived and worked in England for so long that her French accent was impossible to detect, used to say “Charles, how come you can almost pass as fluent when we’re in meetings and talking about collaborative learning, computer conferencing, telecoms, X25 networks and so on, but you’re absolutely hopeless speaking French when we’re engaging someone in general conversation?”. My answer to her was that so long as the context was pretty narrow and you understood what people might be speaking about then meaningful communication isn’t too difficult. It’s quite easy to build a limited vocabulary that is useful in specific situations, and if you have an inkling of what is being said, and what is likely to be said, then you can get by.

In the early and mid-1980s I spent a number of years working on collaborative ‘eLearning’ projects (although we didn’t know them by that name back then) using computer conferencing technology. I was working with academics, teachers, students and workers in the UK, France and Germany and spent long hours in (physical) meeting rooms where multiple languages were being spoken. In France a lot of the discussion took place in French (naturally). My colleague, a Frenchwoman who had lived and worked in England for so long that her French accent was impossible to detect, used to say “Charles, how come you can almost pass as fluent when we’re in meetings and talking about collaborative learning, computer conferencing, telecoms, X25 networks and so on, but you’re absolutely hopeless speaking French when we’re engaging someone in general conversation?”. My answer to her was that so long as the context was pretty narrow and you understood what people might be speaking about then meaningful communication isn’t too difficult. It’s quite easy to build a limited vocabulary that is useful in specific situations, and if you have an inkling of what is being said, and what is likely to be said, then you can get by.

I think Learning professionals can take something from this anecdote in the way they need to approach conversations and communications with others in their organisations.

In simple terms, it’s about effectively communicating in the language of your stakeholder whether you’re speaking to them, writing proposals, giving presentations or delivering reports for their eyes.

If you use your own sometimes arcane professional language it’s likely that much of what you’re saying will simply be lost in translation.

THE DOs an DON’Ts OF WORKING WITH STAKEHOLDERS

Below is an basic set of ‘DOs and DON’Ts’ for Learning professionals when engaging and communicating with stakeholders and others outside the L&D cabal – it’s a simple job-aid or performance support tool.

DOs

1. DO speak the language of your stakeholder/client/customer.

Do this in all your communications with them. If you don’t know their language, you need to learn it – or some of it, such as the key terms they use, before you present anything to them or engage in dialogue. Failure to do this will render you marginalised at best and irrelevant at worst.

You need to understand the drivers that your stakeholders consider important. For example, getting an understanding of some of the subtleties of financial terms. You don’t need to become a financial whizz, but almost every manager with financial responsibility will expect you to know some of the basics – the difference between a balance sheet and a profit and loss account, for instance, or what net present value (npv) is and how your organisation might calculate it – almost every project you’re called in on for learning support will have had its npv calculated, and your proposals had better not increase the costs so that npv takes a downward spiral.

You also need to have some understanding of your organisation’s, and your stakeholder’s, strategic intent – mid-term and longer-term strategy. If you don’t, do a bit of detective work and read some strategy documents on your intranet. Absorb some of the terminology that’s used.

If you’re going to speak to a manger in Sales, do your homework on the current sales figures, know the names of your organisation’s major clients and any prospects that may be on the horizon. If it’s a manager in Development you’re going to meet, ask around beforehand and see if you can identify the major challenges and deadlines that might be keeping her awake at night.

2. DO explain things simply and clearly without using jargon. Make any solution you’re proposing as simple to understand as possible.

Remember, your target is not a learning or performance professional. Develop simple visual representations (but not complex flowcharts) to help make your solution clear. Think three-page proposals rather than 30-pagers. I once presented a 35-page, text-based, solid business plan (at least, I thought it was solid) for an L&D transformation to the HRD of a large corporation. He didn’t even bother reading it. Instead asked me to come back with a PowerPoint deck containing ‘no more than 6 slides with no more than 4 bullet-points on each’. When I distilled my document into the form requested he was happy to make a multi-million dollar L&D transformation/investment decision. I felt it was ‘thin’ and had to get over my ‘PowerPoint-for-everything’ prejudice, but he just wanted a few actionable options on which to make a business decision.

3. DO use terms that focus on business impact and the business results that your learning or performance solution will deliver above all else.

‘Employee Satisfaction’ is less meaningful to a line manager than ‘improved performance’ or ‘greater productivity’. Of course most managers want their teams to have development experiences that are satisfying but the vast majority will value the latter over the former on the basis that a highly performing employee, team or organisation will be more likely to also have higher levels of satisfaction than those that are struggling.

4. DO talk the language of business and organisational value rather than the language of return on investment.

Understand and agree how your stakeholder wants to measure success up-front. You won’t set the metrics, they will. This should be one of the first things you talk to them about and agree on. What will they view as ‘success’?

Find out what a successful outcome looks like to them. Sometimes it may be difficult or even impossible to put a monetary value on the outcomes they are looking for. Your stakeholder may feel that success is wider than can be measured in an ROI calculation. What’s the ROI of email or of air? We wouldn’t even bother to try to determine these. Equally, not every L&D solution can be distilled to numbers on a spreadsheet or it may be equally difficult to draw clear causal links to L&D’s input and actions and the final outputs. Get over it. Agree a set of value-based outcomes and aim for them.

Above all else, get an understanding of what your stakeholder considers success BEFORE you agree anything. Their expectations may be very different to yours and you may have to realign your own, or their expectations may be wildly optimistic and you need to do some ‘reining-in’.

5. DO talk ‘results’ and ‘outcomes’ not inputs.

Your stakeholders generally won’t be interested in the minutiae of L&D/HR processes or whether the instructional design is ‘sound’ or innovative, even if you think that it’s fascinating. Most will simply want to have a high level of confidence that whatever L&D delivers is going to meet or exceed their expectations. Forget about trying to explain the Kirkpatrick measurement model or sound instructional design principals.

Stick to providing a clear set of expected results – setting expectations on what difference they’re likely to see in their people’s performance or attitudes or behaviours.

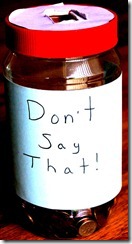

1. DON’T use the language of the Training/ Learning and Development/Talent cabals.

‘Learning’, ‘eLearning’, ‘pedagogy’, ‘instructional design’ ‘needs analysis’ etc. are all useful terms to use in specific circumstances for those in the People Development professions among our own, but they tend to send a cold shiver up the spines of most non-L&D/HR people. Using these terms will leave them cold at best, and wondering whether you understand them at worst.

Remember, always speak their language, not yours. They are your customers. You need to bend and sway with them if you’re going to get them onside.

2. DON’T Complexify.

I didn’t know the word existed until recently either. Here’s a little piece of complexification theory:

If you dress up your learning solutions to make them appear more complex than they are, or if you plan to design sophisticated and complex solutions to address your stakeholder’s problems, they’ll probably mean as much to them as the formula above. Try to keep it as simple as possible. Less moving parts, less chance of breaking.

Remember, your job is to work with your stakeholders to help them solve their business problems and to help the people in their teams be better able to do their jobs. If you approach the challenge correctly they’ll all be on-side with you.

It shouldn’t be rocket science.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

ConsultMember of the Internet Time Alliance and Co-founder of the 70:20:10 Institute, Charles Jennings is a leading thinker and practitioner in learning, development and performance.

Great article thanks Charles. It is so easy to talk in one' own "learning" language when what the business wants to hear (and needs to hear)is how this will improve performance… unless one is talking to LRD people of course! I used to be in IT management and it was very easy to fall into the trap of talking IT instead of business.

Frank Smit, Bridgewater Learning

I recommend the 2010 book "Organizational Intelligence: A Guide to Understanding the Business of Your Organization for HR, Training, and Performance Consulting" by Silber and Kearny. It offers simple, quick tools for getting a handle on stakeholder language and being well-prepared for early meetings.

Thanks, Brian – the Silber and Kearny book is a helpful one. It has worksheets, job aids and practical advice.

Of course it's best to buy the book, but there is a taste of it on Google Books http://bit.ly/hy4hBF